I first found myself enthralled by the Historical Collection at the University Museum when I attended a museum tour last year for the Advanced Museology I course I was enrolled in with Dr. Otto. Clad with our masks and COVID-19 safe protocols, small groups of students were taken around through the museum storage. The second I stepped into the basement, full of historical objects of everyday life, from typewriters, sewing machines, and the largest collection of irons I’ve ever laid my eyes on, I was hooked. My experience working as a graduate student with the University Art Museum (UAM) at NMSU had prepared me for basic object handling and preventative care for objects, but my goal at the University Museum was to expose myself to more experience with handling non-traditional art objects, with more variety of material, size, condition, and historical context.

Collection of historical irons in storage, organized and inventoried by the author.

The Historical Collection at the University Museum is largely related to the history of the Las Cruces and broader border region, extending into Texas and Mexico. Much of the collection was acquired internally through the university, or by donation from local families, alumni, or departments here at NMSU. The history of the collection created an assembly of objects that range from sheet music, embroidery transfer designs, to mining lanterns and drafting tools. Smaller collections of cooking utensils, enamel pots and pans, and hygiene and medical supplies are representative of unique donations that now document significant moments in American history, such as the multi-functional object of a metal pin cushion advertising both “Ely’s Cream Balm” and the U.S. Postal Rates of 1 ounce of letters for 2 cents (1969.16.179, see below).

Metal advertising pin-cushion for Ely's Cream Balm circa 1890s. 1969.16.179, University Museum.

My main goals as I worked through the shelves was to first identify and tag each object with their object number to make the identification and inventorying process simple and quick in the future. This tagging is essential, as it also limits the amount of unnecessary handling of the object. In the past, the object numbers were written in inconspicuous spots–often the base–which over time leads to excess handling of the object in order to identify it. Making the numbers more visibly apparent on tags could be vital for older objects which are frail, or even large heavy steel pots which prove to be quite difficult to lift with one person. Each object had its own unique challenges and needs in regards to preventative care that would protect the object from environmental and human dangers. Layering foam between pans, and wrapping objects in acid-free tissue were some of the next necessary steps in order to best protect these objects over the years. Some objects also were placed in air-tight bags if there were signs of active corrosion, or with many of the historical tins, remnants of the original product still inside.

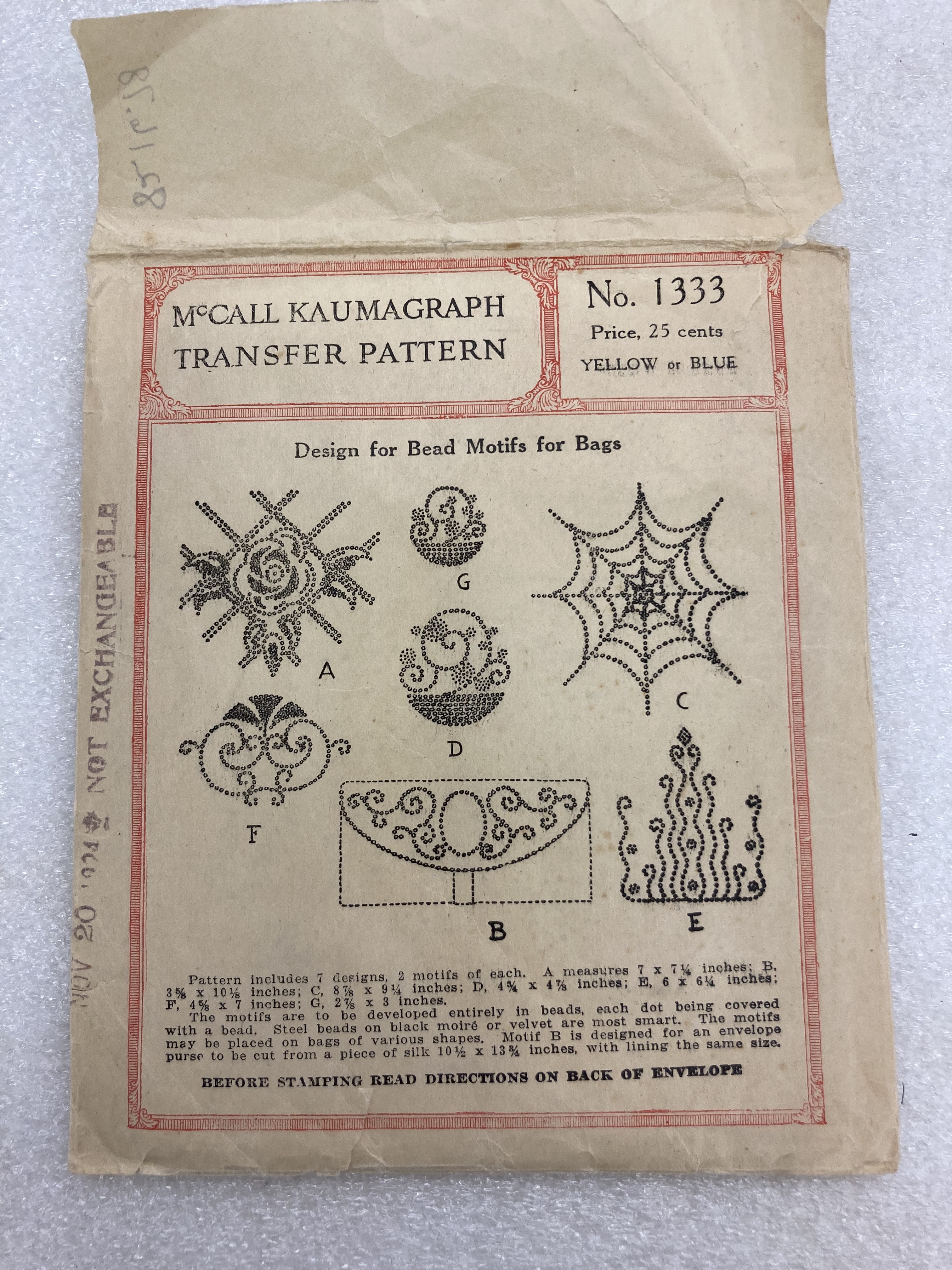

"McCall Kaumagraph Transfer Pattern" designs used for bead motifs for bags, produced in 1924. 1982.16.78, University Museum.

Much of collections management and preventative conservation work, whether it is with historical objects, photographs, or paintings, is thinking about what the object needs in order to provide the safest environment for its life within museum storage. There are reasons why some objects in the world degrade and rust away, while museums are able to keep objects in pristine, workable condition for centuries. The key is always preventative care, and limiting the object’s exposure to extreme environmental factors such as light, humidity and temperature. Acid-free archival tools like foam, tissue paper, and boxes provide an extra layer of safety for the object from outside elements. This emphasis on preventative care is essential for the lasting of the object for future generations to continue to do scholarly research of these important documents of history.

My goal throughout this internship is to use my skills and experience in preventative care to focus on a higher degree of care placed on documentation and storage. The historical collections of the University Museum are expansive, and haven’t always received the most focus and care over decades of time in the museum. The practices of conservation and preventative care in museums are constantly evolving along with the science, and some of the practices seen in museums during the 20th century are no longer enough, or have been deemed harmful to certain objects over time. The steps I’m taking during my time at the University Museum are aimed to protect and preserve these objects, while also making them easier to access for research and future exhibitions.

Beyond all of the knowledge I have acquired regarding handling and preparing materials such as metal, cardboard, and wood, I have also been exposed to such a unique collection of objects that never failed to make me intrigued or sometimes even make me laugh. From the 59 bars of U.S. Army distributed soap from the 1960’s, or containers showcasing the many forms of early laxatives, each object provided me with such an interesting look at the often forgotten moments of daily life.

-Courtney Uldrich, University Museum Graduate Intern, M.A. Student (Art History), NMSU University Art Museum Graduate Assistant